THE WORK OF THE ARTIST

Internet publication by Gijsbert Witkamp

Published: 28 September 2020

Last edit:

Art Making (Non)Sense: Ten Lectures for Students of Art. “An artist is someone who makes objects or events that combine aesthetics and signification and does it well” is about the briefest definition of an artist that I can think of. ‘Well made’ in a broad sense applies to technical competence (material technology and application), design (imagery and signification)and functional adequacy (suited for its use or purpose). Appreciation and valuation of the qualities that class an object as art and hence its maker as an artist vary within and between the socio-cultural setting(s) in which art is made and presented. In a broad and general sense all artists do the same thing, making art, but in any real situation the social position, role, functionality, economics and valuation of artists depend on the art world(s) they are part of.

Artists cannot be ranked from poor to excellent by the objective properties of the art work, though there are aspects of an artist’s work that can be described objectively and assessed reasonably in the art world(s) of its production and/or its distribution. Valuation of artists is subjective and socio-cultural.

Artists by making art contribute to the artistic mindset, the faculty of mind engaged in making and experiencing art. This universal, general function transcends practical applications of art in specific social situations and associated particular functionalities.

Concretely art is to make sense aesthetically and the work of the artist is to make that happen by the creation of imagery that is experienced as real.

PART 1: ARTISTS, SKILLS AND ART WORLDS

Artists cross-culturally

An artist is a human being who makes art. This definition despite its circularity has an important implication: art is defined as human-made, as opposed to being a natural thing. Being human-made art belongs to the realm of culture and social life. This simple fact holds cross-culturally. We may add that though art is located in social life certain arts connect to the metaphysical/spiritual world and their makers or viewers may hold that spiritual forces entered into the creation of these arts. Some have a religious conception saying that The Creation is a work of art by God, or the Gods, or generally the metaphysical entity believed to be the original Creator. In that view all things of the universe can be considered art. I hold on to the man-made definition the reason being that in art man can reflect upon himself whereas natural objects do not reflect upon man – even though we find them aesthetic and meaningful.

Art is universal, though in a society some arts are highlighted and others of minor or no importance. Many cultures, however, have no words that in a direct manner translate to the English art and artist. In ciTonga, the language of the Tonga people of the Gwembe Valley of Zambia, the English art is encompassed by a much broader term: zipangaliko – meaning things made by man, that is, man’s material culture. There is no simple equivalent in ciTonga for the English artist though the language allows a circumscription like ‘someone who makes images well.’ CiTonga, does have words for the technologies or media by means of which arts and crafts are made. There are words for weaving, working in clay, carving and so on. And there is a word approximating the English image: chinzinzimwe. Figurative imagery creation historically is rare amongst Gwembe Tonga, exceptions being clay toys for children and pipe heads for men. For them functional adequacy, in this case practical usefulness, constitutes the goodness of the object and gives rise to aesthetic appreciation. In pottery, however, we also see a major concern with form and decoration (See Witkamp 2013 and Reynolds 1986).

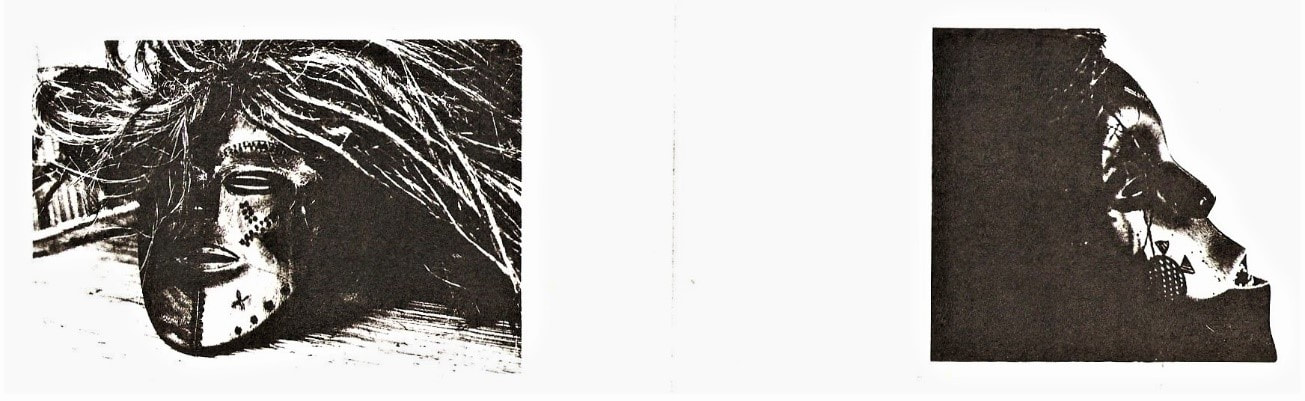

In North Western Zambia and beyond live a cluster of related peoples (‘tribes’) that do have a highly developed tradition of visual imagery. The Luvale, Chokwe, Luchazi, Lunda and Mbunda have a so-called masking tradition mostly referred to as makishi (sg. likishi). Also here we don’t find simple terms corresponding to the English art and artist. But as in Tonga land also the makers of makishi have evaluative criteria: a proper likishi is well made. A well-made likishi must be expressive and meet the formal criteria that allow its identification. Expressiveness in some cases demonstrates conceptions of beauty as in the character Mwana Pwevo, the young woman.

Internet publication by Gijsbert Witkamp

Published: 28 September 2020

Last edit:

Art Making (Non)Sense: Ten Lectures for Students of Art. “An artist is someone who makes objects or events that combine aesthetics and signification and does it well” is about the briefest definition of an artist that I can think of. ‘Well made’ in a broad sense applies to technical competence (material technology and application), design (imagery and signification)and functional adequacy (suited for its use or purpose). Appreciation and valuation of the qualities that class an object as art and hence its maker as an artist vary within and between the socio-cultural setting(s) in which art is made and presented. In a broad and general sense all artists do the same thing, making art, but in any real situation the social position, role, functionality, economics and valuation of artists depend on the art world(s) they are part of.

Artists cannot be ranked from poor to excellent by the objective properties of the art work, though there are aspects of an artist’s work that can be described objectively and assessed reasonably in the art world(s) of its production and/or its distribution. Valuation of artists is subjective and socio-cultural.

Artists by making art contribute to the artistic mindset, the faculty of mind engaged in making and experiencing art. This universal, general function transcends practical applications of art in specific social situations and associated particular functionalities.

Concretely art is to make sense aesthetically and the work of the artist is to make that happen by the creation of imagery that is experienced as real.

PART 1: ARTISTS, SKILLS AND ART WORLDS

Artists cross-culturally

An artist is a human being who makes art. This definition despite its circularity has an important implication: art is defined as human-made, as opposed to being a natural thing. Being human-made art belongs to the realm of culture and social life. This simple fact holds cross-culturally. We may add that though art is located in social life certain arts connect to the metaphysical/spiritual world and their makers or viewers may hold that spiritual forces entered into the creation of these arts. Some have a religious conception saying that The Creation is a work of art by God, or the Gods, or generally the metaphysical entity believed to be the original Creator. In that view all things of the universe can be considered art. I hold on to the man-made definition the reason being that in art man can reflect upon himself whereas natural objects do not reflect upon man – even though we find them aesthetic and meaningful.

Art is universal, though in a society some arts are highlighted and others of minor or no importance. Many cultures, however, have no words that in a direct manner translate to the English art and artist. In ciTonga, the language of the Tonga people of the Gwembe Valley of Zambia, the English art is encompassed by a much broader term: zipangaliko – meaning things made by man, that is, man’s material culture. There is no simple equivalent in ciTonga for the English artist though the language allows a circumscription like ‘someone who makes images well.’ CiTonga, does have words for the technologies or media by means of which arts and crafts are made. There are words for weaving, working in clay, carving and so on. And there is a word approximating the English image: chinzinzimwe. Figurative imagery creation historically is rare amongst Gwembe Tonga, exceptions being clay toys for children and pipe heads for men. For them functional adequacy, in this case practical usefulness, constitutes the goodness of the object and gives rise to aesthetic appreciation. In pottery, however, we also see a major concern with form and decoration (See Witkamp 2013 and Reynolds 1986).

In North Western Zambia and beyond live a cluster of related peoples (‘tribes’) that do have a highly developed tradition of visual imagery. The Luvale, Chokwe, Luchazi, Lunda and Mbunda have a so-called masking tradition mostly referred to as makishi (sg. likishi). Also here we don’t find simple terms corresponding to the English art and artist. But as in Tonga land also the makers of makishi have evaluative criteria: a proper likishi is well made. A well-made likishi must be expressive and meet the formal criteria that allow its identification. Expressiveness in some cases demonstrates conceptions of beauty as in the character Mwana Pwevo, the young woman.

Many cultures presently and/or historically do not differentiate between ‘artist’ or ‘artisan.’ In the western world the modern artist and the role(s) the artists play in society other than that of the artisan is of fairly recent introduction. In English the close association between ‘art’ and craftmanship is demonstrated by using the word art for skill as in the art of beer brewing or bakery: art in the sense of skill is a precondition for making Art in capitals. The linguistic association between art as craftmanship and art as ‘Art’ is common in European languages.

An artist is someone who makes imagery well

Doing it well, art as craft, often is used in a restricted sense: that of technical/material competence. It is about knowledge of materials and techniques and the ability to practically apply materials as they should - including motoric ability. And indeed, workmanship often allows a fairly straightforward manner of assessment and valuation. Things like did the artist use the right paints and were these paints applied well in terms of the technologies standard in his art world usually can be answered with reasonable scientific and professional objectivity. In fact, in the western world is a very advanced art material science and this science is essential in establishing the authenticity of a work of art or perform its restoration – matters which in the case of art by masters may involve millions and sometimes many millions of USD’s.

As an aside I note that while historically in Western art (as generally in all art traditions) appropriate workmanship was a condition for artistic practice notably as of World War II the prominence of craftsmanship has been sidelined in artistic ideologies stressing unfettered spontaneity or in which durability is not considered an essential quality. Much work in that vein is self-destructive in a fairly short time or requires expensive restoration. The relative neglect of material competence in the western art world has had an unfavourable effect on the dissemination of western media and technologies that were introduced in Africa or elsewhere during the colonial days and thereafter. African artists often were/are not taught a sound technology of these initially exotic media (see also Witkamp 2018) resulting in work that suffers from faults like fading or flaking. Another issue is that in many art traditions permanence was not an issue - works were not made to last. Masks, when deteriorated, were replaced by new ones. Or masks were burned at the end of a ceremony or ritual (as in mukanda, the boys initiation ritual of the Luvale people). Lastly, the specialized materials in techniques such as oil or acrylic painting are often not available in countries such as Zambia.

Here I am using ‘making well’ not only to include technical ability but in a broad sense to include design (all that has to do with perceptible imagery and signification), as well as functionality (that what art does or is intended to do in the contexts of its creation and presentation). Making or doing things well in this full sense provides universally criteria for assessment, valuation and appreciation – though the criteria themselves are not universal. Proficiency of these basic arts in combination turn art into ‘Art.’

‘Making things well’ always is located in social contexts and these contexts are located in time and space. The smallest context is that of the artist and the work of art, a face to object productive relationship. This relationship inevitably is imbedded in larger social settings. And the same applies to the observer – work of art relationship, which is one of re-creation. The larger context informs both artist and viewer how to go about making, experiencing and appreciating art. Artists, inevitably build upon an existing tradition(s), as do viewers when viewing art. Sociologists call the totality of all that goes into the making and distribution of art in a particular society an art world (see Becker 1984).

Art worlds are social constructions. Art worlds can be small and simple (as in the Gwembe Tonga case mentioned above), or very large and highly complex (as in any modern state). They have histories that formed them and are increasingly interrelated. And, of course, art worlds are integrated into the larger fabric of society. In that larger fabric art is assigned specific functionalities, such as the commemoration of events by works of art, the expression of certain social or political values, the propagation of religious concepts or ideas, the representation of actual objects or events, the expression of cultural identities or group and status membership, the expression of emotions or states of mind or by being attributed virtues intrinsic to itself. The sorts of art made are accommodated, restrained or facilitated by the existing institutional framework and customary practice of the productive environment. Places lacking international galleries shall have no or little globally oriented art production, in Muslim countries there’ll be no or little figurative art, art in socialist countries tend to glorify the working class, nomads don’t make monumental art and so on.

As noted, the evaluative criteria for ‘doing things well’ vary within and between groups. Example. In the western modern art tradition is a premium on originality and uniqueness. Trailblazers are valued higher than their followers, the epigones. The insistence on innovation and individuation is a major driving force in the development of the western modern art world and ties in with the economy of art. In the west art is an economic commodity subject to the market mechanism of supply and demand. Uniqueness has a price and suits art as valued property or investment. In this context it is vital that each work of art is one of a kind and is attributed to a singular artist. In the graphic arts a single design is printed several times but still the aspect of uniqueness is adhered to as each print of an edition is numbered and signed. The artist has a name and a reputation and hence a market value.

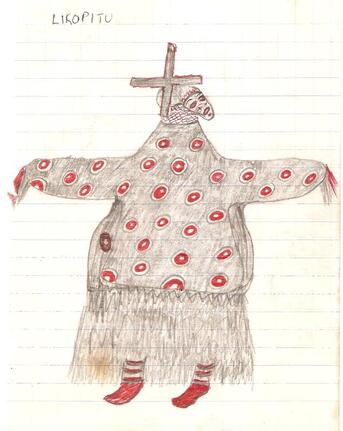

Compare this, for example, with the Luvale tradition of makishi mentioned above (see Witkamp 1987). This tradition is composed of a ‘family’ of masked characters, comparable to characters in a theatrical play. Each character has a name and a role, a prescribed appearance, and specific contexts of performance. The core of this company of masks appears during the initiation for boys, mukanda. The masks are made according to fixed rules, and though these rules change in time – especially as regards materials used - the paramount rule remains: Each likishi must be recognizable as so and so. The dominant value here is conformity to established rules. This does not mean that the system is static, changes and innovation occur as well as individual variation, but in a restricted manner.

An artist is someone who makes imagery well

Doing it well, art as craft, often is used in a restricted sense: that of technical/material competence. It is about knowledge of materials and techniques and the ability to practically apply materials as they should - including motoric ability. And indeed, workmanship often allows a fairly straightforward manner of assessment and valuation. Things like did the artist use the right paints and were these paints applied well in terms of the technologies standard in his art world usually can be answered with reasonable scientific and professional objectivity. In fact, in the western world is a very advanced art material science and this science is essential in establishing the authenticity of a work of art or perform its restoration – matters which in the case of art by masters may involve millions and sometimes many millions of USD’s.

As an aside I note that while historically in Western art (as generally in all art traditions) appropriate workmanship was a condition for artistic practice notably as of World War II the prominence of craftsmanship has been sidelined in artistic ideologies stressing unfettered spontaneity or in which durability is not considered an essential quality. Much work in that vein is self-destructive in a fairly short time or requires expensive restoration. The relative neglect of material competence in the western art world has had an unfavourable effect on the dissemination of western media and technologies that were introduced in Africa or elsewhere during the colonial days and thereafter. African artists often were/are not taught a sound technology of these initially exotic media (see also Witkamp 2018) resulting in work that suffers from faults like fading or flaking. Another issue is that in many art traditions permanence was not an issue - works were not made to last. Masks, when deteriorated, were replaced by new ones. Or masks were burned at the end of a ceremony or ritual (as in mukanda, the boys initiation ritual of the Luvale people). Lastly, the specialized materials in techniques such as oil or acrylic painting are often not available in countries such as Zambia.

Here I am using ‘making well’ not only to include technical ability but in a broad sense to include design (all that has to do with perceptible imagery and signification), as well as functionality (that what art does or is intended to do in the contexts of its creation and presentation). Making or doing things well in this full sense provides universally criteria for assessment, valuation and appreciation – though the criteria themselves are not universal. Proficiency of these basic arts in combination turn art into ‘Art.’

‘Making things well’ always is located in social contexts and these contexts are located in time and space. The smallest context is that of the artist and the work of art, a face to object productive relationship. This relationship inevitably is imbedded in larger social settings. And the same applies to the observer – work of art relationship, which is one of re-creation. The larger context informs both artist and viewer how to go about making, experiencing and appreciating art. Artists, inevitably build upon an existing tradition(s), as do viewers when viewing art. Sociologists call the totality of all that goes into the making and distribution of art in a particular society an art world (see Becker 1984).

Art worlds are social constructions. Art worlds can be small and simple (as in the Gwembe Tonga case mentioned above), or very large and highly complex (as in any modern state). They have histories that formed them and are increasingly interrelated. And, of course, art worlds are integrated into the larger fabric of society. In that larger fabric art is assigned specific functionalities, such as the commemoration of events by works of art, the expression of certain social or political values, the propagation of religious concepts or ideas, the representation of actual objects or events, the expression of cultural identities or group and status membership, the expression of emotions or states of mind or by being attributed virtues intrinsic to itself. The sorts of art made are accommodated, restrained or facilitated by the existing institutional framework and customary practice of the productive environment. Places lacking international galleries shall have no or little globally oriented art production, in Muslim countries there’ll be no or little figurative art, art in socialist countries tend to glorify the working class, nomads don’t make monumental art and so on.

As noted, the evaluative criteria for ‘doing things well’ vary within and between groups. Example. In the western modern art tradition is a premium on originality and uniqueness. Trailblazers are valued higher than their followers, the epigones. The insistence on innovation and individuation is a major driving force in the development of the western modern art world and ties in with the economy of art. In the west art is an economic commodity subject to the market mechanism of supply and demand. Uniqueness has a price and suits art as valued property or investment. In this context it is vital that each work of art is one of a kind and is attributed to a singular artist. In the graphic arts a single design is printed several times but still the aspect of uniqueness is adhered to as each print of an edition is numbered and signed. The artist has a name and a reputation and hence a market value.

Compare this, for example, with the Luvale tradition of makishi mentioned above (see Witkamp 1987). This tradition is composed of a ‘family’ of masked characters, comparable to characters in a theatrical play. Each character has a name and a role, a prescribed appearance, and specific contexts of performance. The core of this company of masks appears during the initiation for boys, mukanda. The masks are made according to fixed rules, and though these rules change in time – especially as regards materials used - the paramount rule remains: Each likishi must be recognizable as so and so. The dominant value here is conformity to established rules. This does not mean that the system is static, changes and innovation occur as well as individual variation, but in a restricted manner.

A likishi like ‘Likopitu’ – helicopter, characterized by the cross on top of its head, - clearly is a recent addition, but its manner of construction follows an established pattern. The makers of makishi are hidden from the spectators and only known to a small group of initiated men. Appreciation of a mask is not directly tied to or derived from the reputation of its maker, certainly not for the public at large and the cost of making one is standardized, not personalized. The makishi artist, maker or performer, is not a public figure with a following on Facebook – he is hidden from the eye of the non-initiated public and the whole business of makishi making is shrouded in mystery and secrecy.

Though ‘doing things well’ may entail different things for different people, groups, communities or societies it is the one aspect of art that can claim universality if we extend the meaning of ‘doing things well’ beyond technical mastery to include visual appearance, signification and functional adequacy. It hence is an important consideration in the cross-cultural study of art. Major anthropologists like Franz Boas (1927) and Gregory Bateson (1973) consider craftsmanship a fundamental condition for the production and appreciation of art, directly associated to aesthetic valuation and sensation. And in the practical world, historically as well as today, accomplished artists are distinguished from learners. The Gwembe Tonga, for example, differentiate between a master artisan and an ordinary practitioner. They explain(ed) the difference by the spiritual connection of the master artisan with one that had died (See E. Colson, 1960: 133, 144-6 and 1971: 210, 217). Such association literally was an inspiring force. At the same time it was understood that the aspiring artisan had to learn and work hard to master his/her trade (Witkamp, 2013).

Artists, critics or scientists well versed in the cross-cultural production and distribution of art tend, broadly speaking, to converge on what is good art, or not so good, or no art at all. There is, I repeat, no objective measuring stick to fully assess art and rank it on some kind of scale. But we can appreciate the effort, the way it is made, even if the art as such is alien to us – meaning its signification and functionality in its context of provenance cannot be followed through. Craftsmanship, cross-culturally, is easier to recognize and appreciate than aesthetic preferences other than those demonstrated by craftmanship itself.

When is art ‘art’ and an ‘artist’ an artist?

Objects made by human beings constitute their material culture. Works of art by members of a certain people or society are elements of the material culture of that group. The interesting question now is whether all skillfully made objects are art or whether works of art are a specific group or class in the universe of all objects that constitute a people’s material culture. The simple answer is to say that a work of art is a work of art if for someone it is experienced as a work of art or is considered to be such. The question then arises what the experience of art is and in what sense it is different from other sorts of experience. The answer to that question is not simple at all and very well may defy satisfactory objective scientific explanation or verification – though at one point brain neurologists will be/are ably to indicate with precision which parts of the brain are engaged during the artistic experience. The social definition of art is based on the conditions and conventions which in a particular context give rise to the classification of an object or event as ‘art.’ Social or institutional definitions of art by-pass the intangible aspects of the artistic experience and valuation. The social definition arises out of the location of art in an art world or art worlds. An art world, as stated above, is socially constructed and exists practically by all that it takes to make and distribute art as well as all art related activities as art criticism, media coverage or public policies. Art, in this approach, is art if it functions as art in an art world, for example by being exhibited in an art gallery, and an artist is an artist if s/he functions or functioned in an art world by making art.

Let me illustrate the social definition of art and artist. I’ll start with a non-contentious example. In Lusaka, Zambia, is the Lechwe Trust, a respectable charity promoting the arts. The Trust has a collection of Zambian modern art of over 400 objects which are from time to time exhibited at its gallery. Going by the social/institutional definition all these objects are works of art by functioning in an art world, irrespective of their individual merits or demerits. Consequently their makers equally so are artists irrespective of their merits or demerits, irrespective of their valuation by outsiders or insiders. Let us now take the contentious hypothetical example of well-made building bricks. Such a brick normally in construction is not considered a work of art, though the building erected by it might. In the western world since the 1950’s forms of art arose labelled ‘installations’ and ‘conceptual art.’ Installations are an assemblage of objects which convey some idea or concept. In this recent tradition it is perfectly feasible that an artist deposits a heap of building bricks in a museum of modern art, be it at random or in some formal arrangement, and simply by being presented as art in ‘a place of art’ the building bricks conceptionally have become art. The practical function of bricks in that context is not irrelevant as it now stands in contrast to its newly acquired dominant artistic functionality. In this situation we are supposed to interpret bricks on display as objects of artistic sensation and contemplation. In the institutional definition of art the display of brinks is art, irrespective of what the viewer thinks of it. Similarly, once an artist has a recognized status as an artist that what he makes in that capacity will be labelled art, irrespective of what the object is, provided it is presented as art.

I agree that the social definition of art is not satisfactory when we are confronted with objects or events in an art world that we may find void of artistic merit or, perhaps, repulsive, but it is practical when it comes to discussion. In art there is no objective measuring stick to distinguish art from non-art. The social definition provides an open approach and furthermore an approach that accepts that there is no hard, fast and universal borderline between art and non-art. It furthermore accommodates changes in the art world easily as when once highly prized art in time is seen as second rate or vice versa; or when new technologies, styles or ideologies emerge.

There is an interesting twist to this seemingly senseless business of depositing building bricks, canned feces or melting ice bars in museums and galleries. You, when you enter a gallery, an art museum or a studio turn on your artistic mindset. You look, literally, at the objects in these locations with different eyes. They become works of art or are considered to be so when you tune in to them as works of art. And, in the case of bricks, the very contrast between the practical and the artistic functionality might be valuable food for thought, prompting us to think about the very question of what art is and what not, or about the need to endow practical objects with aesthetic qualities.

The most famous forerunner of this kind of thing dates back to 1913.

Though ‘doing things well’ may entail different things for different people, groups, communities or societies it is the one aspect of art that can claim universality if we extend the meaning of ‘doing things well’ beyond technical mastery to include visual appearance, signification and functional adequacy. It hence is an important consideration in the cross-cultural study of art. Major anthropologists like Franz Boas (1927) and Gregory Bateson (1973) consider craftsmanship a fundamental condition for the production and appreciation of art, directly associated to aesthetic valuation and sensation. And in the practical world, historically as well as today, accomplished artists are distinguished from learners. The Gwembe Tonga, for example, differentiate between a master artisan and an ordinary practitioner. They explain(ed) the difference by the spiritual connection of the master artisan with one that had died (See E. Colson, 1960: 133, 144-6 and 1971: 210, 217). Such association literally was an inspiring force. At the same time it was understood that the aspiring artisan had to learn and work hard to master his/her trade (Witkamp, 2013).

Artists, critics or scientists well versed in the cross-cultural production and distribution of art tend, broadly speaking, to converge on what is good art, or not so good, or no art at all. There is, I repeat, no objective measuring stick to fully assess art and rank it on some kind of scale. But we can appreciate the effort, the way it is made, even if the art as such is alien to us – meaning its signification and functionality in its context of provenance cannot be followed through. Craftsmanship, cross-culturally, is easier to recognize and appreciate than aesthetic preferences other than those demonstrated by craftmanship itself.

When is art ‘art’ and an ‘artist’ an artist?

Objects made by human beings constitute their material culture. Works of art by members of a certain people or society are elements of the material culture of that group. The interesting question now is whether all skillfully made objects are art or whether works of art are a specific group or class in the universe of all objects that constitute a people’s material culture. The simple answer is to say that a work of art is a work of art if for someone it is experienced as a work of art or is considered to be such. The question then arises what the experience of art is and in what sense it is different from other sorts of experience. The answer to that question is not simple at all and very well may defy satisfactory objective scientific explanation or verification – though at one point brain neurologists will be/are ably to indicate with precision which parts of the brain are engaged during the artistic experience. The social definition of art is based on the conditions and conventions which in a particular context give rise to the classification of an object or event as ‘art.’ Social or institutional definitions of art by-pass the intangible aspects of the artistic experience and valuation. The social definition arises out of the location of art in an art world or art worlds. An art world, as stated above, is socially constructed and exists practically by all that it takes to make and distribute art as well as all art related activities as art criticism, media coverage or public policies. Art, in this approach, is art if it functions as art in an art world, for example by being exhibited in an art gallery, and an artist is an artist if s/he functions or functioned in an art world by making art.

Let me illustrate the social definition of art and artist. I’ll start with a non-contentious example. In Lusaka, Zambia, is the Lechwe Trust, a respectable charity promoting the arts. The Trust has a collection of Zambian modern art of over 400 objects which are from time to time exhibited at its gallery. Going by the social/institutional definition all these objects are works of art by functioning in an art world, irrespective of their individual merits or demerits. Consequently their makers equally so are artists irrespective of their merits or demerits, irrespective of their valuation by outsiders or insiders. Let us now take the contentious hypothetical example of well-made building bricks. Such a brick normally in construction is not considered a work of art, though the building erected by it might. In the western world since the 1950’s forms of art arose labelled ‘installations’ and ‘conceptual art.’ Installations are an assemblage of objects which convey some idea or concept. In this recent tradition it is perfectly feasible that an artist deposits a heap of building bricks in a museum of modern art, be it at random or in some formal arrangement, and simply by being presented as art in ‘a place of art’ the building bricks conceptionally have become art. The practical function of bricks in that context is not irrelevant as it now stands in contrast to its newly acquired dominant artistic functionality. In this situation we are supposed to interpret bricks on display as objects of artistic sensation and contemplation. In the institutional definition of art the display of brinks is art, irrespective of what the viewer thinks of it. Similarly, once an artist has a recognized status as an artist that what he makes in that capacity will be labelled art, irrespective of what the object is, provided it is presented as art.

I agree that the social definition of art is not satisfactory when we are confronted with objects or events in an art world that we may find void of artistic merit or, perhaps, repulsive, but it is practical when it comes to discussion. In art there is no objective measuring stick to distinguish art from non-art. The social definition provides an open approach and furthermore an approach that accepts that there is no hard, fast and universal borderline between art and non-art. It furthermore accommodates changes in the art world easily as when once highly prized art in time is seen as second rate or vice versa; or when new technologies, styles or ideologies emerge.

There is an interesting twist to this seemingly senseless business of depositing building bricks, canned feces or melting ice bars in museums and galleries. You, when you enter a gallery, an art museum or a studio turn on your artistic mindset. You look, literally, at the objects in these locations with different eyes. They become works of art or are considered to be so when you tune in to them as works of art. And, in the case of bricks, the very contrast between the practical and the artistic functionality might be valuable food for thought, prompting us to think about the very question of what art is and what not, or about the need to endow practical objects with aesthetic qualities.

The most famous forerunner of this kind of thing dates back to 1913.

Fountain by Marcel Duchamp has become an iconic ready-made. Fountain needs to be understood as a protest against established academic western art at the time and was deliberately presented as “anti-art.” The provocative Fountain is an actual urinal turned around and flipped 90 degree. Here there is no association by resemblance to its object but one of twisted identity - water the link between its titled designation and its objective functionality. Twisted indeed!

Also well-known is Picasso’s Bull’s Head described as a “found object” made of the steer and saddle of a bicycle which assembled resemble the shape of a real bull’s head. The work may be conceived of as a pun, catch us by surprise and, for some, be appreciated for its aesthetic qualities.

In both cases objects are lifted out of their practical context and viewers are prompted to ‘review’ these objects as art and appreciate formal, creative or aesthetic qualities otherwise not noticed.

Functionality

I have introduced the term functionality by saying that art functions in art worlds. Art does things. It does a number of things but here we are first concerned with what artistic imagery does and therefore with what artists are supposed to make happen. In art the artist is what he does and what he does is make artistic imagery. That is his function.

Now what is the function of visual art? The first and universal answer is that art does that what it takes to make it. In order to make art the artist must have developed the artistic mindset and the art thus made contributes to the creation of the artistic mindset in its viewers.

The practical or applied aspects of the functionality of art and artists arise out of specific contexts in which art is made and presented. Much of medieval European art presents religious subjects and themes, an artist hence is some sort of specialist in religious imagery. There is art that commemorates historic events. There is art that often in symbolic imagery is an element of ritual choreography and practice – possibly some of the oldest art that archeologists have recorded falls in this category. There is art which is iconic for certain situations, states of mind or emotions. There is art made to entertain such as erotic art. And so on. The practical level in specific art worlds directs or sets parameters for what artists can do. The general faculty of artistic creation by the artistic mindset can be conceived of as a meta-function: in case of the visual arts it is the ability to make imagery that combines signification with aesthetics. We discuss the artistic mindset in part 2 of this paper.

In both cases objects are lifted out of their practical context and viewers are prompted to ‘review’ these objects as art and appreciate formal, creative or aesthetic qualities otherwise not noticed.

Functionality

I have introduced the term functionality by saying that art functions in art worlds. Art does things. It does a number of things but here we are first concerned with what artistic imagery does and therefore with what artists are supposed to make happen. In art the artist is what he does and what he does is make artistic imagery. That is his function.

Now what is the function of visual art? The first and universal answer is that art does that what it takes to make it. In order to make art the artist must have developed the artistic mindset and the art thus made contributes to the creation of the artistic mindset in its viewers.

The practical or applied aspects of the functionality of art and artists arise out of specific contexts in which art is made and presented. Much of medieval European art presents religious subjects and themes, an artist hence is some sort of specialist in religious imagery. There is art that commemorates historic events. There is art that often in symbolic imagery is an element of ritual choreography and practice – possibly some of the oldest art that archeologists have recorded falls in this category. There is art which is iconic for certain situations, states of mind or emotions. There is art made to entertain such as erotic art. And so on. The practical level in specific art worlds directs or sets parameters for what artists can do. The general faculty of artistic creation by the artistic mindset can be conceived of as a meta-function: in case of the visual arts it is the ability to make imagery that combines signification with aesthetics. We discuss the artistic mindset in part 2 of this paper.