1 WHAT IS ART? Part 1: In Modern Western Culture.

Internet publication by Gijsbert Witkamp

Published: 3 December 2017

Last edit: 14 November 2018

Art Making Sense: Ten Lectures for Students of Art. In this opening chapter I present key concepts of western modern visual art as a study and a practice. These are derived from linguistic meanings of the word ‘art’ and related terms, the philosophy of art, the notion that art is socially constructed, aesthetics, ethics and the understanding that art is a form of visual signification. I present a basic model of the artistic image as a signifying unit and discuss art as a form of iconic thought, a way of cognizance, combining the principles of visual signification and aesthetics. Art reflects on, constitutes and imagines the human condition. In conclusion I say that the functionality of art is twofold: First in it being a form of aesthetic signification or semiosis and second in the social application of this ability by means of art works and their distribution. The ability of aesthetic signification, that is, the ability to make art, is universal but its application is culture bound. All societies have art, but differ in their art related technologies, ideology and manner of distribution.

Introduction

Most artists depend on their gut feeling in the appreciation of their own work or that of others. And so do art historians, writes eminent art historian Panofsky (1983: 38), calling it “intuitive aesthetic re-creation.” Discussions about what is ‘good art,’ or ‘bad art’ or no art at all tend to be dreary at best and often are phrased in fuzzy or esoteric language. The subject, however, is not without interest or relevance, in part because of its very intransigence; in part because questions about the distinction between art and non-art, artistic boundaries, aesthetics and functionality of art are and have been central in modern western art practice and academic discourse.

Art, language and vocabulary

When we ask: “What is art?” we do so in language and the answer equally so is in language - in this case in English. Language is an essential element of human culture, a vehicle of thought and a major form of human communication. Languages are culture specific and it is important at the onset of the discussion to state explicitly that languages and cultures differ and hence also the manner in which the question “What is art?” is phrased, interpreted and answered. There are, for example, cultures that do not have a readily translatable equivalent to the English ‘art.’ Clifford James says (1988: 196) that art is a changing Western cultural category. Even in the limited context of modern western art there are significant differences in what is or has been accepted as art.

When there is art theory, philosophy of art, art criticism, aesthetics, art technology or other art related discipline or art practice there is a language for it; that is, technical terms, idiom and verbal or written discourse. Language is culture bound and a collection of art related terms is a very good entry into mapping an art world. Such jargon or professional idiom may have unique words only applied in the vocal/verbal art context and, more commonly, words that have a general meaning but in art discourse have acquired a specialized meaning. One meaning of the English verb to glaze is “to coat with or as if with glass,” (Webster 1972: 355). In oil painting to glaze is to apply a thin transparent layer of a pigmented paint medium on a painted surface so as to achieve a special transparent visual effect. Art terminology of one language may not, and often is not, precisely translatable in another language. There is an issue of compatibility or agreement of terms, and sometimes there are no comparable terms and translation becomes des- or circumscription. The English ‘to draw’ in Dutch is ‘tekenen.’ The verb tekenen has the same root as the noun ‘teken’ which in English is ‘sign.’ The verb tekenen translated in English is ‘to draw’ (on a surface). The English to draw is associated with linear movement but not, as in the Dutch word tekenen, with the production of signs. A drawing (object) in Dutch is a tekening, i.e., a product of signification. Dutch therefore has a semantic association between drawing as an activity, as an object and signification which English does not have and therefore is lost in translation. And reversely the English association of drawing and linear movement is absent in Dutch.

The visual art related glossary in all western languages is extensive. We have the terms plastic and visual arts as opposed to arts that are not plastic or visual, or only in part. Visual art, as a category, is composed of a large number of arts distinguished by medium. This material/technical classification has major sub-categories such as graphic art, painting, sculpture or mixed media - all of these having subdivisions. There is a set of terms differentiating arts by function: fine art, applied art, decorative art, commercial art. We distinguish art by style or movement, by provenance (location) and by period. We have amateur and professional art, public art and private art, religious or profane art, popular or folk or high art, and more. We can consider the large variety of such characteristics or attributes as variables. The combination of the variables in an overall scheme or paradigm delivers a classificatory instrument in which each art can be placed in a system of relationships to other arts. The style labelled impressionism makes sense not only because of its intrinsic stylistic properties but also by its differences to other stylistic -isms. The significance of an impressionistic painting is not only in its impressionism but also in it not being an expressionistic (or other stylistically defined) work. We can look at these terms as the elements of a classificatory frame work within the arts.

The core of the art glossary is the word art itself. In asking “What is art?” we are engaging ourselves in a classificatory operation in which we differentiate between art and non-art. The term art in English dictionaries embraces a number of meanings. I summarize first the art entry of Webster’s Seventh New Collegiate Dictionary (1972: 49), as follows:

A broader linguistic investigation including other western European languages may widen or narrow the scope of the English definitions but broadly the following shared meanings emerge:

What emerges in the western cultural sphere across different languages is an art concept associated to similar semantics and practices. Skill (as masterly ability, technical competence, method and rules of application of a technique) gives rise to art objects (such objects being creative, engaging the imagination and a sense of aesthetics) which are made in a number or artistic disciplines such as painting, sculpture or graphic art. This semantic complex retains the classical Greek view in which art is perceived as a craft or technique. In modern western art the understanding that excellent craftsmanship is a precondition for the production of art has been supplemented or replaced by an ideology that stresses expressiveness, spontaneity, or the conceptual aspects of the work of art.

Let us now turn to the Philosophy of Art article in the internet edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica so as to get a respectable conventional contemporary understanding of what art is. Its author, the American art theorist John Hospers, writes (2016) that a work of art, in a broad sense, is considered to be “a human made object presented to be contemplated for its own sake.” In this definition a natural object is not a work of art, though natural objects by the hand and mind of man are and can be transformed into art. The article does not say why a natural object should not be classified as a work of art and this renders the definition somewhat arbitrary. The implication, however, is that art exclusively is considered to be a product of human culture. Yet you may ask yourself why a painted rose should be a work of art and the natural object that inspired the painter is not. Now what happens when an artist collects natural objects and displays them as art – as happens in so-called conceptual art or in ready-mades? Art or non-art?

Internet publication by Gijsbert Witkamp

Published: 3 December 2017

Last edit: 14 November 2018

Art Making Sense: Ten Lectures for Students of Art. In this opening chapter I present key concepts of western modern visual art as a study and a practice. These are derived from linguistic meanings of the word ‘art’ and related terms, the philosophy of art, the notion that art is socially constructed, aesthetics, ethics and the understanding that art is a form of visual signification. I present a basic model of the artistic image as a signifying unit and discuss art as a form of iconic thought, a way of cognizance, combining the principles of visual signification and aesthetics. Art reflects on, constitutes and imagines the human condition. In conclusion I say that the functionality of art is twofold: First in it being a form of aesthetic signification or semiosis and second in the social application of this ability by means of art works and their distribution. The ability of aesthetic signification, that is, the ability to make art, is universal but its application is culture bound. All societies have art, but differ in their art related technologies, ideology and manner of distribution.

Introduction

Most artists depend on their gut feeling in the appreciation of their own work or that of others. And so do art historians, writes eminent art historian Panofsky (1983: 38), calling it “intuitive aesthetic re-creation.” Discussions about what is ‘good art,’ or ‘bad art’ or no art at all tend to be dreary at best and often are phrased in fuzzy or esoteric language. The subject, however, is not without interest or relevance, in part because of its very intransigence; in part because questions about the distinction between art and non-art, artistic boundaries, aesthetics and functionality of art are and have been central in modern western art practice and academic discourse.

Art, language and vocabulary

When we ask: “What is art?” we do so in language and the answer equally so is in language - in this case in English. Language is an essential element of human culture, a vehicle of thought and a major form of human communication. Languages are culture specific and it is important at the onset of the discussion to state explicitly that languages and cultures differ and hence also the manner in which the question “What is art?” is phrased, interpreted and answered. There are, for example, cultures that do not have a readily translatable equivalent to the English ‘art.’ Clifford James says (1988: 196) that art is a changing Western cultural category. Even in the limited context of modern western art there are significant differences in what is or has been accepted as art.

When there is art theory, philosophy of art, art criticism, aesthetics, art technology or other art related discipline or art practice there is a language for it; that is, technical terms, idiom and verbal or written discourse. Language is culture bound and a collection of art related terms is a very good entry into mapping an art world. Such jargon or professional idiom may have unique words only applied in the vocal/verbal art context and, more commonly, words that have a general meaning but in art discourse have acquired a specialized meaning. One meaning of the English verb to glaze is “to coat with or as if with glass,” (Webster 1972: 355). In oil painting to glaze is to apply a thin transparent layer of a pigmented paint medium on a painted surface so as to achieve a special transparent visual effect. Art terminology of one language may not, and often is not, precisely translatable in another language. There is an issue of compatibility or agreement of terms, and sometimes there are no comparable terms and translation becomes des- or circumscription. The English ‘to draw’ in Dutch is ‘tekenen.’ The verb tekenen has the same root as the noun ‘teken’ which in English is ‘sign.’ The verb tekenen translated in English is ‘to draw’ (on a surface). The English to draw is associated with linear movement but not, as in the Dutch word tekenen, with the production of signs. A drawing (object) in Dutch is a tekening, i.e., a product of signification. Dutch therefore has a semantic association between drawing as an activity, as an object and signification which English does not have and therefore is lost in translation. And reversely the English association of drawing and linear movement is absent in Dutch.

The visual art related glossary in all western languages is extensive. We have the terms plastic and visual arts as opposed to arts that are not plastic or visual, or only in part. Visual art, as a category, is composed of a large number of arts distinguished by medium. This material/technical classification has major sub-categories such as graphic art, painting, sculpture or mixed media - all of these having subdivisions. There is a set of terms differentiating arts by function: fine art, applied art, decorative art, commercial art. We distinguish art by style or movement, by provenance (location) and by period. We have amateur and professional art, public art and private art, religious or profane art, popular or folk or high art, and more. We can consider the large variety of such characteristics or attributes as variables. The combination of the variables in an overall scheme or paradigm delivers a classificatory instrument in which each art can be placed in a system of relationships to other arts. The style labelled impressionism makes sense not only because of its intrinsic stylistic properties but also by its differences to other stylistic -isms. The significance of an impressionistic painting is not only in its impressionism but also in it not being an expressionistic (or other stylistically defined) work. We can look at these terms as the elements of a classificatory frame work within the arts.

The core of the art glossary is the word art itself. In asking “What is art?” we are engaging ourselves in a classificatory operation in which we differentiate between art and non-art. The term art in English dictionaries embraces a number of meanings. I summarize first the art entry of Webster’s Seventh New Collegiate Dictionary (1972: 49), as follows:

- A skill (in several senses; of performance based on learning, of ingenuity in adapting natural things to man’s use, a system of rules or method for performing particular actions, the systematic application of rules for a specific result).

- A branch of learning (the study of art, the liberal arts).

- The conscious use of skill, taste and creative imagination in the production of aesthetic objects, the works so produced.

- Cunning, craftiness including its negative associations.

- The expression or application of creative skill and imagination, especially through a visual medium such as painting or sculpture, the works produced in this way.

- The various branches of creative activity (i.e., painting &c.).

- Subjects of study primarily concerned with human culture.

- A skill in a specified thing.

A broader linguistic investigation including other western European languages may widen or narrow the scope of the English definitions but broadly the following shared meanings emerge:

- Art as a skill in a variety of senses: craftsmanship, technical competence, creative design, method and techniques (as in painting).

- Art as a general term for artistic disciplines (such as painting &c.).

- Art as a class of objects (made by any of the artistic disciplines) that are creative, aesthetic and require imagination.

What emerges in the western cultural sphere across different languages is an art concept associated to similar semantics and practices. Skill (as masterly ability, technical competence, method and rules of application of a technique) gives rise to art objects (such objects being creative, engaging the imagination and a sense of aesthetics) which are made in a number or artistic disciplines such as painting, sculpture or graphic art. This semantic complex retains the classical Greek view in which art is perceived as a craft or technique. In modern western art the understanding that excellent craftsmanship is a precondition for the production of art has been supplemented or replaced by an ideology that stresses expressiveness, spontaneity, or the conceptual aspects of the work of art.

Let us now turn to the Philosophy of Art article in the internet edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica so as to get a respectable conventional contemporary understanding of what art is. Its author, the American art theorist John Hospers, writes (2016) that a work of art, in a broad sense, is considered to be “a human made object presented to be contemplated for its own sake.” In this definition a natural object is not a work of art, though natural objects by the hand and mind of man are and can be transformed into art. The article does not say why a natural object should not be classified as a work of art and this renders the definition somewhat arbitrary. The implication, however, is that art exclusively is considered to be a product of human culture. Yet you may ask yourself why a painted rose should be a work of art and the natural object that inspired the painter is not. Now what happens when an artist collects natural objects and displays them as art – as happens in so-called conceptual art or in ready-mades? Art or non-art?

Art generally and fine art in particular in the Hospers definition above are differentiated from human made objects having an utilitarian function. A work of art, such as “the Yellow House” by Van Gogh, therefore is distinguished from a utilitarian object such as a brush Van Gogh used to paint with by the brush not being a work of art. The painting is considered to be an end in itself (i.e., “to be contemplated for its own sake”) whereas a brush Van Gogh used is a means to an end. We do not contemplate it for its own sake. Also here is a query: is there always such a clear cut difference between the utilitarian and the non-utilitarian? There are so many examples of utilitarian objects that also are art. And what about non-utilitarian functionalities? Works of art usually function in an economic circuit, may present religious of other ideological imagery, serve to indicate a certain life style or position in society, celebrate a certain event &c. Don’t these associations not enter into the appreciation of a work of art?

These common notions, concepts and ideas as to “What is Art” are those of the modern western visual art tradition – modernity in western art starting with impressionism roughly as of mid-19th century. There are other notions as well within the same broad tradition but at the onset let us first concern ourselves with mainstream basic concepts.

The functionality of art, in modern mainstream western art theory, as noted above, is located in itself as art objects are created to be contemplated for their own sake. Art thus constitutes a distinct domain of human activity in which its imaginary scope is not or should not be fettered by its inclusion or close association with other domains of human life, be these practical or ideological or otherwise. This approach clearly advocates artistic freedom but tells us little as to why we would like to contemplate objects merely for their own sake.

Fine art is art in a narrow sense of the term, writes Hospers and such art is composed of man-made objects “responded to aesthetically.” Panofsky likewise writes (1983: 37) that a work of art is a “man-made object demanding to be experienced aesthetically.” Aesthetic experiences, however, cover a much broader area than the arts. Natural objects or phenomena may be perceived as having aesthetic qualities or give rise to aesthetic experience; and the same holds for man-made non-art objects or events, the ones having a utilitarian (or other) function.

Summarizing the above notions on art and the aesthetic I provisionally summarize as follows:

Modern western visual art constitutes a distinct domain of human activity the central concern of which is the construction of imagery and its presentation as objects of contemplation and aesthetic experience.

The first issue is whether this statement, in the context of Western art theory and practice, is sufficiently complete and precise. The answer is that it requires elaboration so as to be meaningful. The next question is whether such elaboration satisfies a cross-cultural approach to (visual) art. The latter question is discussed in chapter 2, but it does not harm to know now that it does not have satisfying cross-cultural validity.

Let us commence with the notion that art constitutes 'a distinct domain' of human society. The term implies that a) artistic activities are identifiable, and b) that the totality of these activities are interrelated and constitute what sociologists call an art world (see Becker, 1984). Art historians and anthropologists of art conventionally speak about an art tradition, a term which has stronger historical associations. The concept 'art world' highlights that art is socially embedded.

Art World

The “art world” approach to understanding art emphasizes that art and all that goes with it (the totality of its production, distribution, conceptualisation and any other associated activity) is socially constructed. It is in this precise sense that natural objects in their natural environment are not considered art, even though they may be experienced aesthetically and are endowed with meaning by the viewer. The classification of certain objects, events or activities as art arises out of these manifestations taking place in the context of an art world. Such classification hence is social and occurs in a particular society (group, community) in time and space.

As an illustration of the latter: classificatory criteria implied or mentioned above by Hospers regarding art are: man-made (as opposed to natural objects or phenomena), presentation (as opposed to objects that cannot or are not intended to be exposed) and contemplation for its own sake (as opposed to having utilitarian or other functions). Fine art more over “is to be responded to aesthetically” (as opposed to objects not made to elicit such a response). These current classificatory factors (and others not mentioned here) are the outcome of a particular history during which art conceptions and practices changed significantly. This constellation cannot lay claim to universal validity.

Each work of art is made in a social environment that produces and distributes certain arts. Conventionally such embedding is called an art tradition. The term tradition emphasizes that art has a history and is handed down from generation to generation. Any work of art is the outcome of and contributor to a particular history; firstly that of the artist as a participant of the tradition that brought the art forth. The artist’s mind is not a tabula rasa, but is programmed by history, or, rather his/her exposure to it; and so is the mind of the viewer.

Sociologists and anthropologists of art study art in its social context, its art world. Art has meaning and functionality only in such a context. People generally and artists as well take the world as it is for granted. For artists it is important to realize that they literally have been and are socially formed and informed by the (art) environment they live in and have been exposed to. That environment supplies them with art materials, art works to be seen at specific venues and locations, learning facilities, ways to present their work, the economy of production and distribution; values, conceptions and ideologies attached to art – including a western mindset that emphasizes originality and uniqueness.

A corollary of this setup (art as entrenched in institutions, institutional procedure, academic or popular discourse, customs and habits or conventions) is that what is socially presented as art in places and at occasions designated as appropriate venues for art tends to be accepted as art – that is, all that is on show in galleries, museums, art manifestations or at specific public places or events or is publicised by reputable media. In this sense an art world delivers a social definition of what is art and what is not. In Janet Wolff’s formulation (1983: 78): “The institutional theory of art defines art by reference to those objects and practices which are given the status of art by the society in which they exist.” Mitchel (1986) with justification might comment that the institutional definition of art not so much defines what art is as when art is art.

The so-called institutional approach is enforced and to some extent justified by the fact that objects presented in a gallery or museum environment are viewed by the viewer as art, be such objects works of art in a conventional sense or a heap of bricks ordinarily used for construction. More specifically: the heap of bricks, by the museum environment in which they are placed, are viewed with what Panofsky calls (1983:34) “aesthetic intent,” and which I preferably call the artistic mindset. The art museum entry, with metaphoric efficacy, serves as a switch turning the viewer on into the 'aesthetic mode.' Janet Wolff speaks of the aesthetic attitude. She writes (ibid, p. 73) “that we may look at anything in the aesthetic attitude. ‘Art’ is either that which is produced in this attitude or that which is experienced thus.” Famous examples of this phenomenon are Picasso’s bicycle steer, Duchamp’s urinal or Andy Warhol’s Brillo boxes. In these instances objects are lifted out of their ordinary context and presented as art by placing them in an environment directed towards artistic appreciation and valuation. Inevitably these provocative displays raise the question of what is art and what not.

The functionality of art, in modern mainstream western art theory, as noted above, is located in itself as art objects are created to be contemplated for their own sake. Art thus constitutes a distinct domain of human activity in which its imaginary scope is not or should not be fettered by its inclusion or close association with other domains of human life, be these practical or ideological or otherwise. This approach clearly advocates artistic freedom but tells us little as to why we would like to contemplate objects merely for their own sake.

Fine art is art in a narrow sense of the term, writes Hospers and such art is composed of man-made objects “responded to aesthetically.” Panofsky likewise writes (1983: 37) that a work of art is a “man-made object demanding to be experienced aesthetically.” Aesthetic experiences, however, cover a much broader area than the arts. Natural objects or phenomena may be perceived as having aesthetic qualities or give rise to aesthetic experience; and the same holds for man-made non-art objects or events, the ones having a utilitarian (or other) function.

Summarizing the above notions on art and the aesthetic I provisionally summarize as follows:

Modern western visual art constitutes a distinct domain of human activity the central concern of which is the construction of imagery and its presentation as objects of contemplation and aesthetic experience.

The first issue is whether this statement, in the context of Western art theory and practice, is sufficiently complete and precise. The answer is that it requires elaboration so as to be meaningful. The next question is whether such elaboration satisfies a cross-cultural approach to (visual) art. The latter question is discussed in chapter 2, but it does not harm to know now that it does not have satisfying cross-cultural validity.

Let us commence with the notion that art constitutes 'a distinct domain' of human society. The term implies that a) artistic activities are identifiable, and b) that the totality of these activities are interrelated and constitute what sociologists call an art world (see Becker, 1984). Art historians and anthropologists of art conventionally speak about an art tradition, a term which has stronger historical associations. The concept 'art world' highlights that art is socially embedded.

Art World

The “art world” approach to understanding art emphasizes that art and all that goes with it (the totality of its production, distribution, conceptualisation and any other associated activity) is socially constructed. It is in this precise sense that natural objects in their natural environment are not considered art, even though they may be experienced aesthetically and are endowed with meaning by the viewer. The classification of certain objects, events or activities as art arises out of these manifestations taking place in the context of an art world. Such classification hence is social and occurs in a particular society (group, community) in time and space.

As an illustration of the latter: classificatory criteria implied or mentioned above by Hospers regarding art are: man-made (as opposed to natural objects or phenomena), presentation (as opposed to objects that cannot or are not intended to be exposed) and contemplation for its own sake (as opposed to having utilitarian or other functions). Fine art more over “is to be responded to aesthetically” (as opposed to objects not made to elicit such a response). These current classificatory factors (and others not mentioned here) are the outcome of a particular history during which art conceptions and practices changed significantly. This constellation cannot lay claim to universal validity.

Each work of art is made in a social environment that produces and distributes certain arts. Conventionally such embedding is called an art tradition. The term tradition emphasizes that art has a history and is handed down from generation to generation. Any work of art is the outcome of and contributor to a particular history; firstly that of the artist as a participant of the tradition that brought the art forth. The artist’s mind is not a tabula rasa, but is programmed by history, or, rather his/her exposure to it; and so is the mind of the viewer.

Sociologists and anthropologists of art study art in its social context, its art world. Art has meaning and functionality only in such a context. People generally and artists as well take the world as it is for granted. For artists it is important to realize that they literally have been and are socially formed and informed by the (art) environment they live in and have been exposed to. That environment supplies them with art materials, art works to be seen at specific venues and locations, learning facilities, ways to present their work, the economy of production and distribution; values, conceptions and ideologies attached to art – including a western mindset that emphasizes originality and uniqueness.

A corollary of this setup (art as entrenched in institutions, institutional procedure, academic or popular discourse, customs and habits or conventions) is that what is socially presented as art in places and at occasions designated as appropriate venues for art tends to be accepted as art – that is, all that is on show in galleries, museums, art manifestations or at specific public places or events or is publicised by reputable media. In this sense an art world delivers a social definition of what is art and what is not. In Janet Wolff’s formulation (1983: 78): “The institutional theory of art defines art by reference to those objects and practices which are given the status of art by the society in which they exist.” Mitchel (1986) with justification might comment that the institutional definition of art not so much defines what art is as when art is art.

The so-called institutional approach is enforced and to some extent justified by the fact that objects presented in a gallery or museum environment are viewed by the viewer as art, be such objects works of art in a conventional sense or a heap of bricks ordinarily used for construction. More specifically: the heap of bricks, by the museum environment in which they are placed, are viewed with what Panofsky calls (1983:34) “aesthetic intent,” and which I preferably call the artistic mindset. The art museum entry, with metaphoric efficacy, serves as a switch turning the viewer on into the 'aesthetic mode.' Janet Wolff speaks of the aesthetic attitude. She writes (ibid, p. 73) “that we may look at anything in the aesthetic attitude. ‘Art’ is either that which is produced in this attitude or that which is experienced thus.” Famous examples of this phenomenon are Picasso’s bicycle steer, Duchamp’s urinal or Andy Warhol’s Brillo boxes. In these instances objects are lifted out of their ordinary context and presented as art by placing them in an environment directed towards artistic appreciation and valuation. Inevitably these provocative displays raise the question of what is art and what not.

Duchamp’s urinal was initially rejected at a Dada art exhibition in Paris, a remarkable event as the Dada movement was geared towards the creation of anti-art – meaning art against the art establishment. “The idea was to question the very notion of Art, and the adoration of art, which Duchamp found "unnecessary"" (Wikipedia, page on Marcel Duchamp). Today the same object is considered pivotal in re-thinking art and what art should do – indeed iconically posing the question 'what is art' as its subject and theme.

Ready-mades often have aesthetic qualities which are highlighted by their presentation as works of art but are ignored in daily practice. So-called conceptual art may or may not explore aesthetic qualities of the materials it is composed of or the manner of arrangement of these components. Yet also for such art applies that the viewer turns on (hopefully) his/her artistic mindset to take the work in as art. As an aside to the above: switching on the artistic mindset by entering an appropriate context (as a gallery) does not automatically result in personal acceptance of the shown objects or events as art. There might be and is, also among an informed public, revolt, disgust, disapproval or other form of non-acceptance; and if such persists the work shall cease to be displayed. Remarkably at the time of writing in the USA historical statues of the confederation days and the civil war are being removed from public places as they are perceived as tokens of white supremacy. More on personal validation below.

The social definition of art (as objects functioning in an art world) frees the student and researcher of art of having to impose 'aesthetic criteria' on the objects of study. Instead the researcher should look for aesthetic valuation or criteria present in the art world in question - as these are held by artists, audiences, writers, art specialists or other actors in a given art scene. This approach is not only essential in the cross-cultural study of art but also for any complex (i.e., non-homogeneous art world). A corollary of the art world approach is that the personal art/aesthetic preferences of the viewer/student/researcher are (at least in theory) outside the definition of the scope of investigation. The unsolvable/problematic issue of the aesthetic in art is circumvented and itself now is subject/object of research. This must be as:

In art are no universal objective criteria as to what is art or what is not, neither do we have universal objective criteria in aesthetics.

By 'objective' I mean material qualities that can be measured or at least identified that are pertinent to the object itself, irrespective of its perception or valuation by the observer. Yes, we can indeed say that an object made of oil paints applied to a canvas is an oil painting but that technical/material classification does not provide the object with the status of art, the latter requires social validation. Such validation may be motivated by all sorts of reasons and what works in one place at one time may not work elsewhere or at another time – art is a changing cultural category indeed!

The art world concept provides a general design for description of an art scene. Players, institutions, manner of distribution, etc. can be mapped on this broad paradigm – it being tailored towards specific research interests of the student or writer. Such research interest of course entails the engagement of specific theories and methodologies and these shall influence the data collection and processing.

An immediate effect of the study of art in a social context is the awareness that the idea and ideal of 'unfettered artistic expression' in practice is restricted by the economy and politics of production and distribution, the market place that is, as well as by ideological and social factors. In fact, when writers on art state that, the observer, in order to fully appreciate a work of art, should have 'auxiliary information' (that is, relevant social, personal or historical information) such simply means that contextual factors enter into the art design and its interpretation. This view by some is extended to include knowledge of the artist’s intentions and personal appreciation: we should experience/understand the work of art in the manner the artist intended.

Fuzzy art concept

Does the art world approach sort out the issue of what in a society is to be included as art and what is not? Yes and no. First, not all art in a specific environment is open to the public or accessible in some form that engages social validation. Second, and more important, is that though the social approach is instrumental to define the field such definition cannot set absolute borders. There’ll be a grey area, there are indeterminate or controversial cases, the art world itself is in permanent flux. Third, it has been suggested that art (as a concept pertaining to art objects) eludes precise definition, it is a fuzzy or open textured concept (see Sieber 1989: 432-434 and Ladd 1989: 418-421), which in principle cannot be defined with scientific exactness. Sieber suggests that a set of variables be adopted not all of which are applicable in a specific situation but the ones that are constitute discriminating criteria. Such criteria should not be ethnocentric but cross-culturally valid. Fuzziness does not render the art concept useless – in daily life we use countless concepts that are not defined or cannot be defined in a scientifically precise manner but which nevertheless are effectively used in communication as there is sufficient common understanding of what is meant by such terms. This common understanding is based on a practice, on what in the manner of Wittgenstein could be called the language game of everyday life. But do note that these language games differ as languages differ.

Social versus individual definition

Art, at the individual level, engages a particular sort of experience and for many true art is true art only because of such experience. In the opening paragraph I referred to the gut feeling of artists and the “intuitive aesthetic recreation” of a sophisticated art historian. The art that moves you, touches you, captures you, is art that to you is great art, ART in capitals, validated by the experience that it arouses. Art, Tolstoy stated over 100 years ago (1975: 228), must be infectious in order to accomplish its mission. Personal experiential validation is essential in art and may be at odds with the socially accepted in a particular art world. At this point I note: a) that the manner of personal validation of art inevitably is influenced and often determined by one’s exposure to art, that is in specific social settings including specific manners of learning or familiarization and b) that such personal appreciation may and often does require 'auxiliary knowledge,' the kind of stuff art historians specialise in, so as to understand the work better. Panofsky describes very well (1983: 40-41) how his “intuitive aesthetic recreation” is followed by an intellectual examination and exploration in which a particular work of art is compared to others and placed in its art historical context. Van Gogh’s The Yellow House for those raised in modern Western art is a fascinating, perhaps even a magical painting which we can appreciate without knowing anything about the physical yellow house that was the material subject of the painting or of the mental state van Gogh was in when painting. The substance of the work, so to speak, is enhanced if we know that that Van Gogh lived in the yellow house and had prepared it in anticipation for the arrival of Gauguin whom he expected to stay there and work with him. No doubt these great expectations informed the manner Van Gogh painted his image of The Yellow House – indeed the yellow house is not about a physical building but about a station or state of mind.

Normative criteria: Aesthetics and ethics

Aesthetics and ethics are branches of philosophy. Ethics of daily life, in brief, is about living and doing things right; and in philosophy more precisely about thinking what is right and what is wrong. Aesthetics, I am inclined to say, is about living well; but that would not be quite correct. The problems in defining aesthetics are similar and even related to those of defining art. It is dealt with in chapter 4. What we retain here is that the English aesthetics is derived from the Greek aisthetikos, meaning pertaining to the senses, or “the conditions of sense perception” (Firth 1992: 15). The term aesthetics is not reserved to art, it is applied to any man-made or natural object or event that is perceived to have aesthetic qualities. Panofsky (1983: 34): “It is possible to experience every object, natural or man-made, aesthetically.” In art aesthetics hence concerns the perception and appreciation of art and often is taken to mean that what makes art beautiful. Not all art, however, is (experienced as) beautiful or pleasant yet all art has aesthetic significance.

Ready-mades often have aesthetic qualities which are highlighted by their presentation as works of art but are ignored in daily practice. So-called conceptual art may or may not explore aesthetic qualities of the materials it is composed of or the manner of arrangement of these components. Yet also for such art applies that the viewer turns on (hopefully) his/her artistic mindset to take the work in as art. As an aside to the above: switching on the artistic mindset by entering an appropriate context (as a gallery) does not automatically result in personal acceptance of the shown objects or events as art. There might be and is, also among an informed public, revolt, disgust, disapproval or other form of non-acceptance; and if such persists the work shall cease to be displayed. Remarkably at the time of writing in the USA historical statues of the confederation days and the civil war are being removed from public places as they are perceived as tokens of white supremacy. More on personal validation below.

The social definition of art (as objects functioning in an art world) frees the student and researcher of art of having to impose 'aesthetic criteria' on the objects of study. Instead the researcher should look for aesthetic valuation or criteria present in the art world in question - as these are held by artists, audiences, writers, art specialists or other actors in a given art scene. This approach is not only essential in the cross-cultural study of art but also for any complex (i.e., non-homogeneous art world). A corollary of the art world approach is that the personal art/aesthetic preferences of the viewer/student/researcher are (at least in theory) outside the definition of the scope of investigation. The unsolvable/problematic issue of the aesthetic in art is circumvented and itself now is subject/object of research. This must be as:

In art are no universal objective criteria as to what is art or what is not, neither do we have universal objective criteria in aesthetics.

By 'objective' I mean material qualities that can be measured or at least identified that are pertinent to the object itself, irrespective of its perception or valuation by the observer. Yes, we can indeed say that an object made of oil paints applied to a canvas is an oil painting but that technical/material classification does not provide the object with the status of art, the latter requires social validation. Such validation may be motivated by all sorts of reasons and what works in one place at one time may not work elsewhere or at another time – art is a changing cultural category indeed!

The art world concept provides a general design for description of an art scene. Players, institutions, manner of distribution, etc. can be mapped on this broad paradigm – it being tailored towards specific research interests of the student or writer. Such research interest of course entails the engagement of specific theories and methodologies and these shall influence the data collection and processing.

An immediate effect of the study of art in a social context is the awareness that the idea and ideal of 'unfettered artistic expression' in practice is restricted by the economy and politics of production and distribution, the market place that is, as well as by ideological and social factors. In fact, when writers on art state that, the observer, in order to fully appreciate a work of art, should have 'auxiliary information' (that is, relevant social, personal or historical information) such simply means that contextual factors enter into the art design and its interpretation. This view by some is extended to include knowledge of the artist’s intentions and personal appreciation: we should experience/understand the work of art in the manner the artist intended.

Fuzzy art concept

Does the art world approach sort out the issue of what in a society is to be included as art and what is not? Yes and no. First, not all art in a specific environment is open to the public or accessible in some form that engages social validation. Second, and more important, is that though the social approach is instrumental to define the field such definition cannot set absolute borders. There’ll be a grey area, there are indeterminate or controversial cases, the art world itself is in permanent flux. Third, it has been suggested that art (as a concept pertaining to art objects) eludes precise definition, it is a fuzzy or open textured concept (see Sieber 1989: 432-434 and Ladd 1989: 418-421), which in principle cannot be defined with scientific exactness. Sieber suggests that a set of variables be adopted not all of which are applicable in a specific situation but the ones that are constitute discriminating criteria. Such criteria should not be ethnocentric but cross-culturally valid. Fuzziness does not render the art concept useless – in daily life we use countless concepts that are not defined or cannot be defined in a scientifically precise manner but which nevertheless are effectively used in communication as there is sufficient common understanding of what is meant by such terms. This common understanding is based on a practice, on what in the manner of Wittgenstein could be called the language game of everyday life. But do note that these language games differ as languages differ.

Social versus individual definition

Art, at the individual level, engages a particular sort of experience and for many true art is true art only because of such experience. In the opening paragraph I referred to the gut feeling of artists and the “intuitive aesthetic recreation” of a sophisticated art historian. The art that moves you, touches you, captures you, is art that to you is great art, ART in capitals, validated by the experience that it arouses. Art, Tolstoy stated over 100 years ago (1975: 228), must be infectious in order to accomplish its mission. Personal experiential validation is essential in art and may be at odds with the socially accepted in a particular art world. At this point I note: a) that the manner of personal validation of art inevitably is influenced and often determined by one’s exposure to art, that is in specific social settings including specific manners of learning or familiarization and b) that such personal appreciation may and often does require 'auxiliary knowledge,' the kind of stuff art historians specialise in, so as to understand the work better. Panofsky describes very well (1983: 40-41) how his “intuitive aesthetic recreation” is followed by an intellectual examination and exploration in which a particular work of art is compared to others and placed in its art historical context. Van Gogh’s The Yellow House for those raised in modern Western art is a fascinating, perhaps even a magical painting which we can appreciate without knowing anything about the physical yellow house that was the material subject of the painting or of the mental state van Gogh was in when painting. The substance of the work, so to speak, is enhanced if we know that that Van Gogh lived in the yellow house and had prepared it in anticipation for the arrival of Gauguin whom he expected to stay there and work with him. No doubt these great expectations informed the manner Van Gogh painted his image of The Yellow House – indeed the yellow house is not about a physical building but about a station or state of mind.

Normative criteria: Aesthetics and ethics

Aesthetics and ethics are branches of philosophy. Ethics of daily life, in brief, is about living and doing things right; and in philosophy more precisely about thinking what is right and what is wrong. Aesthetics, I am inclined to say, is about living well; but that would not be quite correct. The problems in defining aesthetics are similar and even related to those of defining art. It is dealt with in chapter 4. What we retain here is that the English aesthetics is derived from the Greek aisthetikos, meaning pertaining to the senses, or “the conditions of sense perception” (Firth 1992: 15). The term aesthetics is not reserved to art, it is applied to any man-made or natural object or event that is perceived to have aesthetic qualities. Panofsky (1983: 34): “It is possible to experience every object, natural or man-made, aesthetically.” In art aesthetics hence concerns the perception and appreciation of art and often is taken to mean that what makes art beautiful. Not all art, however, is (experienced as) beautiful or pleasant yet all art has aesthetic significance.

Equating aesthetics practically with a sense of beauty hence is too restrictive; some authors employ concepts like patterning, harmony or formal qualities (such as balance, rhythm) as giving rise to aesthetic experience or appreciation. Members of the same society, furthermore, may differ in their manner of aesthetic appreciation and such differences often are even greater in cross-cultural validation. Public aesthetic appreciation of art changes in time: the early work of artists like Malevich or Kandinsky had few admirers, Van Gogh during his life sold only one painting and Modigliani’s superb painted nudes at the time of first exposition just after WW I caused scandal and were considered obscene. I discuss aesthetics in some details in followings texts on skill and what artists do. For the time being we’ll just stick to the term aesthetic in an open ended manner. Art students do have and in fact consciously develop their sense of aesthetics and if such is done in a social rather than idiosyncratic manner aesthetics can be handled practically without spelling out exactly what it is or could be. In scientific writing (or thinking) one states precisely in what sense the term is being applied – be it as a personal understanding or as perceived to be practiced by a particular group (that is of the participants); if applied to art: to the manner a work of art is experienced, to certain aspects of it or its allover concept in the art world(s) where it is located; or as a contribution to the philosophy of art.

Ethics

Modigliani’s work, as written above, was considered obscene at the time of its first display in the 1910’s and 20’s; not despite of but because of the compelling beauty of his superbly painted nudes; the verdict was a moral or ethical one and for those who hold that what is morally bad must also be aesthetically bad the aesthetic judgement was equally damming despite or because of the incredible sensuality of the painting.

Ethics

Modigliani’s work, as written above, was considered obscene at the time of its first display in the 1910’s and 20’s; not despite of but because of the compelling beauty of his superbly painted nudes; the verdict was a moral or ethical one and for those who hold that what is morally bad must also be aesthetically bad the aesthetic judgement was equally damming despite or because of the incredible sensuality of the painting.

Note that at the time, as of the 1910’s, much experimental work had been shown (i.e., Picasso, Matisse, Kandinsky, Malevich and others) that did not arouse calls for censorship.

Obligatory conformity in the arts to state policy was imposed in the Soviet Union under Stalin in the thirties. Artists who considered themselves revolutionaries in art in a once revolutionary society fell in disgrace or were sidelined. Their art by the State now was labelled 'bourgeois' or elitists. Abstract experiments became exceptions in an artistic landscape now dominated by works done in a style known as social realism. Art had to celebrate labour, the labour class and the communist state in imagery that could be grasped without artistic understanding or imagination.

These examples demonstrate that moral or ethical judgments are affected, determined or dictated by 'external' factors, be these political, religious, philosophical, ideological, economic or social and that within a single society simultaneously conflicting positions may be taken as regards to what is right or wrong in the arts. It is a regular occurrence today in the USA (and other countries) that individuals or organisations request the removal of works of art on public display as these are deemed offensive by one group or another because of their imagery, historical, social or ideological associations or objectionable behaviour of the producing artist.

Each artist, in any case, irrespective of one’s individual position, explicitly or implicitly makes decisions as regards subject matter, style, technique, mode of distribution or publication that have an ethical bearing. Each artist when going public therefore evokes the question why s/he does what for whom. More on this in a dedicated chapter.

Functional definitions

Objects or non-material events can be defined in different ways – practically we choose those that are relevant in a particular context or discourse. A western functional definition of art focuses on what art objects do socially and psychologically, and to find that out we need to investigate particular art worlds. A common modern view, cited above as formulated by Hospers is that art objects are to be contemplated “for their own sake” and are to be responded to aesthetically. Scholars and practitioners agree that a work of art must have 'artistic merit' and in this sense is to be perceived for its own sake - though they may disagree on what constitutes or gives rise to artistic merit. For many the definition of 'artistic merit' narrowly defined as pleasing sensory sensation is deficient – art must have a mission larger than the provision of what Marcel Duchamp called retinal pleasure. We may admire the formal beauty of an object but that does not turn a urinal into a work of art as Duchamp states by his 1917 Fountain. Or did it?

I distinguish two sorts of function. One sort is intrinsic to art and hence is about imagery and imagery formation. Intrinsic function concerns art experienced and interpreted in its visual aspect. Intrinsic function embraces all that which has to with art as a percept, conventions of imagery formation (i.e., geometric perspective as a manner of the creation of a three dimensional representation on a two dimensional support), conventions of interpretation of imagery (e.i., symbolism, generally the relation between sign-image and representation or meaning) and style (as a meta set of properties applicable to a particular corpus of art). Intrinsic function, in a dangerous analogy, covers both ‘art as a language,’ meaning a set of rules and conventions and all the expressions made by these rules and conventions – the works of art.

Associated functions are all the functions that issue from art participating in particular situations, contexts or activities. Art may, and usually does, take part in economic transactions, hence has economic value in an art market of one sort or another. Art, as noted above, may be engaged in political ideology or religion and ritual. Art may be made to entertain or relax or to commemorate certain events or situations. Art sometimes is made to commemorate that what is presented as imagery. And so on. Such associated functions generate associated or connotative meaning. Any functional context (i.e., social, economic, religious, &c.) directs or limits imagery, manner of imagery formation (‘style’ and material construction), distribution, access and appreciation. A religious painting in the Christian tradition invariably has a biblical subject; generally choices are made suited to purpose, occasion and target market. A work of art thus may signify membership of a certain group or religion, social status, adherence to a certain life style &c. Associated function and connotative meaning issue from distribution of art, intrinsic function is all that which is internal to the imagery of art.

External factors, however, do or may influence appreciation and experience of the imagery: knowing that the simple print you are looking at is a Rembrandt, or that the painting that superficially could be taken to be a historic icon in the Russian Orthodox Church tradition in fact is Salvator Mundi, attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, to date the most costly work of art ever sold, may literally cause you to look at these works with different eyes. Reversely, imagery may have an effect on functional context when elements of that context are the subject/theme/object/referent of the art work as in religious or politically charged art.

Art as visual signification and iconic thought

In art we see all sorts of imagery. Some imagery realistically depicts something that exists or existed and other imagery presents reality in a free manner, some imagery depicts imaginary scenes realistically and others do so freely, some imagery does not seem to have an object in the material visual world at all but presents a mental state/feeling/emotion, some imagery is set to explicitly deliver a message and other imagery does not seem to have a message at all, some imagery is constructed to present ideas or conceptions and others offer little more than a ride for the eyes, some images are made of conventional signs or symbols, other does not have conventional signs and much imagery combines a number of the possibilities mentioned above. In all this variety is one constant: the very fact of imagery and imagery formation itself. We therefore, in the final section of this chapter, try to understand how this imagery formation takes place and how it is constituted and conclude by focusing on art as a manner of aesthetic visual signification. Aesthetic signification, in my understanding, is the prime and specific function of art as productive activity, product, perception and object of interpretation.

In this perspective we shall firstly define a work of art as a signifying object; that is, an object made to signify and have significance. Seeing a work of art engages a signifying experience. I choose a semiotic model because the various sorts of image functions (such as commemoration, iconic symbolization, evocation of feelings and aesthetic sensation) can be subsumed under a more general functionality, that of signification and semiosis – semiosis being the process of establishing a relation between a sign, its object (that what the sign refers to) and its interpretant or meaning (see Eco 1979: 15-16). Questions such as what art is and what it is about are best answered by an approach that covers both “what art does” and “how it does it.” In conclusion of this introductory chapter we shall synoptically present the semiotic approach and return to it in a more technical and detailed manner in chapters 3.

The study of signs in the American tradition is called semiotics and in the French tradition semiology. Each of these strands has its own intellectual history and theoretical positions. Here we briefly introduce the American variety as it in some ways is more suited to the understanding of art as aesthetic signification. Semiotics was founded by the American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914). Peirce’s simple definition of the sign is simple indeed. He says that a sign is a sign if it stands for something it is not in some aspect or capacity for someone. Its elaboration is remarkably complex – we’ll save that for chapter three. Pierce’s definition of the sign includes a personal signifying experience of the viewer/recipient, not necessarily embedded in collective codification defining the relation between the visual sign, that what the sign represents and its interpretation. In his definition any percept/object/event can be a sign be it natural or man-made as long as it is perceived as a sign by someone. Furthermore, different observers may attach different signification to the same thing that they have perceived as a sign. Eco (1979: 16) says that signs can be anything that can stand for something else on the grounds of a previously established social convention. Semiotics, Eco continues, thus is (or can be) concerned with ordinary objects insofar as they participate in semiosis. Art objects can and should be considered semiotic objects; and, we argue of a special type as they are deliberately made to signify. Yes, you may argue that an object is perceived and valued as a work of art by an observer also when its maker did not do so intentionally, and indeed, such may occur. But almost all art is produced by artists who are professional specialists, skilled in their profession, who make art deliberately and intentionally. I shall follow Pierce’s broad definition as it better allows for individual signification of the viewer or maker of the art work than a definition that centres on a collective code or convention as is the case in semiology.

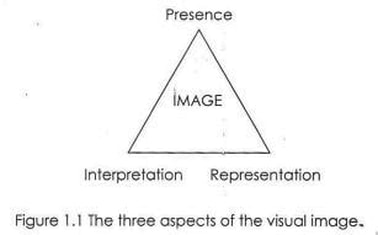

In Pierce a sign is a unit composed of three elements: the observable sign, its object (that what the sign represents)and its interpretant (its meaning, the description of the relation between the visible sign and its object). Note that this trinity may apply to a single sign, such as the word ‘chair’ or a complex sign (such as a painted portrait). We are now extrapolating this basic definition to the level of artistic imagery. We shall consider a work of art to consist of three interrelated elements: the Presence, the Representation, and the Interpretation. As follows:

Obligatory conformity in the arts to state policy was imposed in the Soviet Union under Stalin in the thirties. Artists who considered themselves revolutionaries in art in a once revolutionary society fell in disgrace or were sidelined. Their art by the State now was labelled 'bourgeois' or elitists. Abstract experiments became exceptions in an artistic landscape now dominated by works done in a style known as social realism. Art had to celebrate labour, the labour class and the communist state in imagery that could be grasped without artistic understanding or imagination.

These examples demonstrate that moral or ethical judgments are affected, determined or dictated by 'external' factors, be these political, religious, philosophical, ideological, economic or social and that within a single society simultaneously conflicting positions may be taken as regards to what is right or wrong in the arts. It is a regular occurrence today in the USA (and other countries) that individuals or organisations request the removal of works of art on public display as these are deemed offensive by one group or another because of their imagery, historical, social or ideological associations or objectionable behaviour of the producing artist.

Each artist, in any case, irrespective of one’s individual position, explicitly or implicitly makes decisions as regards subject matter, style, technique, mode of distribution or publication that have an ethical bearing. Each artist when going public therefore evokes the question why s/he does what for whom. More on this in a dedicated chapter.

Functional definitions

Objects or non-material events can be defined in different ways – practically we choose those that are relevant in a particular context or discourse. A western functional definition of art focuses on what art objects do socially and psychologically, and to find that out we need to investigate particular art worlds. A common modern view, cited above as formulated by Hospers is that art objects are to be contemplated “for their own sake” and are to be responded to aesthetically. Scholars and practitioners agree that a work of art must have 'artistic merit' and in this sense is to be perceived for its own sake - though they may disagree on what constitutes or gives rise to artistic merit. For many the definition of 'artistic merit' narrowly defined as pleasing sensory sensation is deficient – art must have a mission larger than the provision of what Marcel Duchamp called retinal pleasure. We may admire the formal beauty of an object but that does not turn a urinal into a work of art as Duchamp states by his 1917 Fountain. Or did it?

I distinguish two sorts of function. One sort is intrinsic to art and hence is about imagery and imagery formation. Intrinsic function concerns art experienced and interpreted in its visual aspect. Intrinsic function embraces all that which has to with art as a percept, conventions of imagery formation (i.e., geometric perspective as a manner of the creation of a three dimensional representation on a two dimensional support), conventions of interpretation of imagery (e.i., symbolism, generally the relation between sign-image and representation or meaning) and style (as a meta set of properties applicable to a particular corpus of art). Intrinsic function, in a dangerous analogy, covers both ‘art as a language,’ meaning a set of rules and conventions and all the expressions made by these rules and conventions – the works of art.

Associated functions are all the functions that issue from art participating in particular situations, contexts or activities. Art may, and usually does, take part in economic transactions, hence has economic value in an art market of one sort or another. Art, as noted above, may be engaged in political ideology or religion and ritual. Art may be made to entertain or relax or to commemorate certain events or situations. Art sometimes is made to commemorate that what is presented as imagery. And so on. Such associated functions generate associated or connotative meaning. Any functional context (i.e., social, economic, religious, &c.) directs or limits imagery, manner of imagery formation (‘style’ and material construction), distribution, access and appreciation. A religious painting in the Christian tradition invariably has a biblical subject; generally choices are made suited to purpose, occasion and target market. A work of art thus may signify membership of a certain group or religion, social status, adherence to a certain life style &c. Associated function and connotative meaning issue from distribution of art, intrinsic function is all that which is internal to the imagery of art.

External factors, however, do or may influence appreciation and experience of the imagery: knowing that the simple print you are looking at is a Rembrandt, or that the painting that superficially could be taken to be a historic icon in the Russian Orthodox Church tradition in fact is Salvator Mundi, attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, to date the most costly work of art ever sold, may literally cause you to look at these works with different eyes. Reversely, imagery may have an effect on functional context when elements of that context are the subject/theme/object/referent of the art work as in religious or politically charged art.

Art as visual signification and iconic thought

In art we see all sorts of imagery. Some imagery realistically depicts something that exists or existed and other imagery presents reality in a free manner, some imagery depicts imaginary scenes realistically and others do so freely, some imagery does not seem to have an object in the material visual world at all but presents a mental state/feeling/emotion, some imagery is set to explicitly deliver a message and other imagery does not seem to have a message at all, some imagery is constructed to present ideas or conceptions and others offer little more than a ride for the eyes, some images are made of conventional signs or symbols, other does not have conventional signs and much imagery combines a number of the possibilities mentioned above. In all this variety is one constant: the very fact of imagery and imagery formation itself. We therefore, in the final section of this chapter, try to understand how this imagery formation takes place and how it is constituted and conclude by focusing on art as a manner of aesthetic visual signification. Aesthetic signification, in my understanding, is the prime and specific function of art as productive activity, product, perception and object of interpretation.

In this perspective we shall firstly define a work of art as a signifying object; that is, an object made to signify and have significance. Seeing a work of art engages a signifying experience. I choose a semiotic model because the various sorts of image functions (such as commemoration, iconic symbolization, evocation of feelings and aesthetic sensation) can be subsumed under a more general functionality, that of signification and semiosis – semiosis being the process of establishing a relation between a sign, its object (that what the sign refers to) and its interpretant or meaning (see Eco 1979: 15-16). Questions such as what art is and what it is about are best answered by an approach that covers both “what art does” and “how it does it.” In conclusion of this introductory chapter we shall synoptically present the semiotic approach and return to it in a more technical and detailed manner in chapters 3.

The study of signs in the American tradition is called semiotics and in the French tradition semiology. Each of these strands has its own intellectual history and theoretical positions. Here we briefly introduce the American variety as it in some ways is more suited to the understanding of art as aesthetic signification. Semiotics was founded by the American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914). Peirce’s simple definition of the sign is simple indeed. He says that a sign is a sign if it stands for something it is not in some aspect or capacity for someone. Its elaboration is remarkably complex – we’ll save that for chapter three. Pierce’s definition of the sign includes a personal signifying experience of the viewer/recipient, not necessarily embedded in collective codification defining the relation between the visual sign, that what the sign represents and its interpretation. In his definition any percept/object/event can be a sign be it natural or man-made as long as it is perceived as a sign by someone. Furthermore, different observers may attach different signification to the same thing that they have perceived as a sign. Eco (1979: 16) says that signs can be anything that can stand for something else on the grounds of a previously established social convention. Semiotics, Eco continues, thus is (or can be) concerned with ordinary objects insofar as they participate in semiosis. Art objects can and should be considered semiotic objects; and, we argue of a special type as they are deliberately made to signify. Yes, you may argue that an object is perceived and valued as a work of art by an observer also when its maker did not do so intentionally, and indeed, such may occur. But almost all art is produced by artists who are professional specialists, skilled in their profession, who make art deliberately and intentionally. I shall follow Pierce’s broad definition as it better allows for individual signification of the viewer or maker of the art work than a definition that centres on a collective code or convention as is the case in semiology.

In Pierce a sign is a unit composed of three elements: the observable sign, its object (that what the sign represents)and its interpretant (its meaning, the description of the relation between the visible sign and its object). Note that this trinity may apply to a single sign, such as the word ‘chair’ or a complex sign (such as a painted portrait). We are now extrapolating this basic definition to the level of artistic imagery. We shall consider a work of art to consist of three interrelated elements: the Presence, the Representation, and the Interpretation. As follows:

Later on we shall elaborate this primitive model and refine each dimension of this tripartite unity. For the time being let us start off with simple working definitions of the image constituents. The presence is the art object and its perception. The representation is all that which is represented visually in the work of art. These conventionally are actual objects (material things and events that exist or existed) as well as ideas, concept and emotions. The interpretation of the art work concerns its all-over concept considered as in interrelated whole. The concept directly is an interpretation of the visual and representative aspects of the art work, an interpretation informed by and expanded by considering the art word in appropriate contexts.

We should be mindful at the onset that the image unit is (or can be thought to be) an element of several universes of related images. Such as the oeuvre of the artist that made a specific work of art, or of the art world where it is functioning, or any other contextualising criterium. These different contexts or sets generate different sorts of meaning that may help to understand what the art work is about, how and why it was constructed or what its stylistic features are and mean.

But we are taking off with this elementary unit of imagery formation, one model triangle and shall expand it in chapter three. Let us illustrate the model by this photograph of Ossip Zadkine’s monumental sculpture The Destroyed City (in Dutch: Verscheurde Stad), 1953.

Photo 6. The Destroyed City. Ossip Zadkine. Bronze, 1953.

Source of image: Wikipedia.

The Presence is the art object, i.e., the sculpture, as an object to be perceived and as perceived. The representation in this case is that of a human body, torn and in a gesture of deep distress. The interpretation is that the sculpture symbolises the destruction of the city of Rotterdam and the death and maiming of its citizens by a German air bombardment in 1940, at the onset of WW II in the Netherlands. The figure stands for the city, its inhabitants and despair by the destruction of the bombing. There are other levels and modes of analysis but this is the basic description of a statue that indeed has become iconic for a particular situation and in its iconicity arises above the situational peculiarities that gave rise to its creation and thus has become a general symbol for human suffering. The expressiveness of the sculpture – in the western culture - can be felt without knowing the specifics that gave rise to its creation, i.e., the bombing of Rotterdam, though such knowledge is required in Panofsky’s manner of iconology. This example neatly fits Pierce’s aesthetics as discussed by Nicole Everaerts-Desmedt in which she develops the concept iconic thought. A work of art, she says, constitutes and is perceived as an iconic thought. She writes (2006: 1) “The interpretation of a work of art guides the receiver towards an iconic thought, which encompasses a total quality of feeling – Peirce’s pure icon.” And, in the same aesthetic, (ibid. p. 2): “Art makes qualities of feeling intelligible by means of iconic signs. Art thus is a path to cognizance, a means for intelligibility to grow.” The focus of the artistic effort is to give intelligible visual form to qualities feeling – indeed literally making sense. The aesthetic, in Peirce, is that what is admirable in itself and what is admirable in itself is a reasonable feeling. “A work of art is self-adequate when it presents itself as a reasonable feeling, when it is the intelligible expression of a synthesized quality of feeling” (ibid. p. 2). Note the stress on art as the ‘intelligible expression of feeling'!

Has our three-in-one model general applicability in static visual art? Well, without a presence – the perceivable art object – there is no art in any social sense. But what about that what is represented, the object or referent of the visual image? The identification of what the artistic image ‘represents’ (refers to, is supposed to evoke) often is not straightforward at all. And if that is the case, neither is its interpretation. Let us look at an example in which the relation between image – representation and interpretation is not so simple.

We should be mindful at the onset that the image unit is (or can be thought to be) an element of several universes of related images. Such as the oeuvre of the artist that made a specific work of art, or of the art world where it is functioning, or any other contextualising criterium. These different contexts or sets generate different sorts of meaning that may help to understand what the art work is about, how and why it was constructed or what its stylistic features are and mean.

But we are taking off with this elementary unit of imagery formation, one model triangle and shall expand it in chapter three. Let us illustrate the model by this photograph of Ossip Zadkine’s monumental sculpture The Destroyed City (in Dutch: Verscheurde Stad), 1953.

Photo 6. The Destroyed City. Ossip Zadkine. Bronze, 1953.

Source of image: Wikipedia.