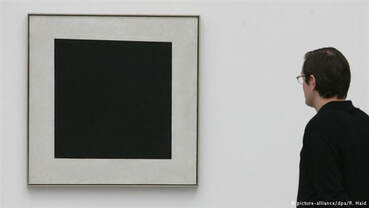

Illustration in header: Black Square, Kazimir Malevich, 1913.

(note: the crackle is not part of the original design which is just a plain square!)

Internet publication by Gijsbert Witkamp

First published 5 June 2019.

You may argue that being deprived of electricity by the national provider is not one of the worst things to live with in these bleak times – it cuts our bills (hopefully) and in my case reduces the smell of cup cakes emanating from my neighbour’s house, a residential high cost location he has turned into a full time bakery. On the other hand the present load shedding of four hours daily might just augur bigger things to come. And yes, there are unpleasant side effects: faltering internet connection and erratic water supply. Plus the nasty feeling that ZESCO in response to the rejection of its proposed 300% tariff increase now is telling us that you get what you pay for and if you don’t pay enough you don’t get enough of the stuff that energizes modern life. And beyond these considerations is the profound impact on the well-being of the people and the national economy.

Lenin, the founder of the Soviet Union, famously said some hundred years ago “communism is Soviet power plus electrification.” Electricity was to energize and symbolize the transformation of a backward rural society into a progressive industrialising modern state.

The first abstract paintings were made just before the Bolshevik revolution of 1917. Malevich, a Russian, is one of the founders of pure abstract art, an art conceived to have no association with objective, perceived or perceptible reality and such lack of representation was to create a sense of pure emotion or feeling in the observer of the work of art. Malevich’s Black Square is iconic for this ideology and some say literally deliberately so as it was displayed high in a corner of a room, a location reserved for icons of the Russian Orthodox Church. You don’t have to be a semiotician to understand that pure abstract art, dissociated from any objective reality, fully non-representational cannot exist, abstract art is based on an ideological fallacy. We are born to make sense of what we perceive and invent meaning even where not intended. But that is another story. Let’s return to the Black Square. What made Malevich make this painting? One of a series in the same style, bearing titles such as Red Square or White on White. The broader answer is that Malevich lived in revolutionary times and that included the arts. The old order, tsarist Russia, was about to be violently destroyed to be replaced by a society in which the working class was to come first rather than a small clique of aristocrats, oligarchs and clergy men whose wealth and comfort arose out of the merciless exploitation of the common man – now the proletariat. The dissociation of the painted image with an easily identifiable external reality, yes just its mere possibility, greatly exited Malevich and other pioneers of abstract art. This art was new and sensed as a liberation from the repressive yoke of representation.

Let us say that Malevich’s art was a revolutionary act. But why did he start out in black? And which black did he use? Well, at the time there were several blacks, all carbon based: ivory black, grape pit black and lamp black (soot). Of these lamp black is the most likely as paraffin or oil lamps were the common source of illumination prior to the electrification so strongly pursued by Lenin. And thus we see an unexpected connection between blackness, which is the absence of light, and light itself: the burning of oil simultaneously creates absolute blackness and abundant radiation, fire being the transforming agent.

And that gets us back to ZESCO. We have to be in the dark to see the light. There are lessons to be learned. I am looking at two recent events both published on the Net. The first is a statement by ZESCO management that the cost of the production of electricity has increased as a result of the rehabilitation of (some of) its plants. Surely that requires an explanation. What exactly are these extra costs? New yet inefficient machines? The cost of finance? Is this another undercover debt trap operation to get a foothold in one of our vital enterprises, ZNBC style? The other one is a World Bank report stating that certain rehabilitation works were commissioned to a certain company that had submitted a fraudulent tender. Yet we have a tender board the members of which ought to be men and women of high competence and integrity. Such things cannot go unnoticed. Of course, if you want to be blind to this sort of thing you’ll never see the light. And if that is the case simply opt for a 24 hour / day black out. Let Malevich have a ball with you. He’ll give you black light.

(note: the crackle is not part of the original design which is just a plain square!)

Internet publication by Gijsbert Witkamp

First published 5 June 2019.

You may argue that being deprived of electricity by the national provider is not one of the worst things to live with in these bleak times – it cuts our bills (hopefully) and in my case reduces the smell of cup cakes emanating from my neighbour’s house, a residential high cost location he has turned into a full time bakery. On the other hand the present load shedding of four hours daily might just augur bigger things to come. And yes, there are unpleasant side effects: faltering internet connection and erratic water supply. Plus the nasty feeling that ZESCO in response to the rejection of its proposed 300% tariff increase now is telling us that you get what you pay for and if you don’t pay enough you don’t get enough of the stuff that energizes modern life. And beyond these considerations is the profound impact on the well-being of the people and the national economy.

Lenin, the founder of the Soviet Union, famously said some hundred years ago “communism is Soviet power plus electrification.” Electricity was to energize and symbolize the transformation of a backward rural society into a progressive industrialising modern state.

The first abstract paintings were made just before the Bolshevik revolution of 1917. Malevich, a Russian, is one of the founders of pure abstract art, an art conceived to have no association with objective, perceived or perceptible reality and such lack of representation was to create a sense of pure emotion or feeling in the observer of the work of art. Malevich’s Black Square is iconic for this ideology and some say literally deliberately so as it was displayed high in a corner of a room, a location reserved for icons of the Russian Orthodox Church. You don’t have to be a semiotician to understand that pure abstract art, dissociated from any objective reality, fully non-representational cannot exist, abstract art is based on an ideological fallacy. We are born to make sense of what we perceive and invent meaning even where not intended. But that is another story. Let’s return to the Black Square. What made Malevich make this painting? One of a series in the same style, bearing titles such as Red Square or White on White. The broader answer is that Malevich lived in revolutionary times and that included the arts. The old order, tsarist Russia, was about to be violently destroyed to be replaced by a society in which the working class was to come first rather than a small clique of aristocrats, oligarchs and clergy men whose wealth and comfort arose out of the merciless exploitation of the common man – now the proletariat. The dissociation of the painted image with an easily identifiable external reality, yes just its mere possibility, greatly exited Malevich and other pioneers of abstract art. This art was new and sensed as a liberation from the repressive yoke of representation.

Let us say that Malevich’s art was a revolutionary act. But why did he start out in black? And which black did he use? Well, at the time there were several blacks, all carbon based: ivory black, grape pit black and lamp black (soot). Of these lamp black is the most likely as paraffin or oil lamps were the common source of illumination prior to the electrification so strongly pursued by Lenin. And thus we see an unexpected connection between blackness, which is the absence of light, and light itself: the burning of oil simultaneously creates absolute blackness and abundant radiation, fire being the transforming agent.

And that gets us back to ZESCO. We have to be in the dark to see the light. There are lessons to be learned. I am looking at two recent events both published on the Net. The first is a statement by ZESCO management that the cost of the production of electricity has increased as a result of the rehabilitation of (some of) its plants. Surely that requires an explanation. What exactly are these extra costs? New yet inefficient machines? The cost of finance? Is this another undercover debt trap operation to get a foothold in one of our vital enterprises, ZNBC style? The other one is a World Bank report stating that certain rehabilitation works were commissioned to a certain company that had submitted a fraudulent tender. Yet we have a tender board the members of which ought to be men and women of high competence and integrity. Such things cannot go unnoticed. Of course, if you want to be blind to this sort of thing you’ll never see the light. And if that is the case simply opt for a 24 hour / day black out. Let Malevich have a ball with you. He’ll give you black light.